Customer reviews on sites such as Yelp and Google My Business (formerly Google Places for Business) are a growing concern for most companies. They often have little choice whether they are listed on these sites. Then one day a review appears at the top of a Google search of their company’s name. And it stays there, whether it is authentic, verifiable or anonymous.

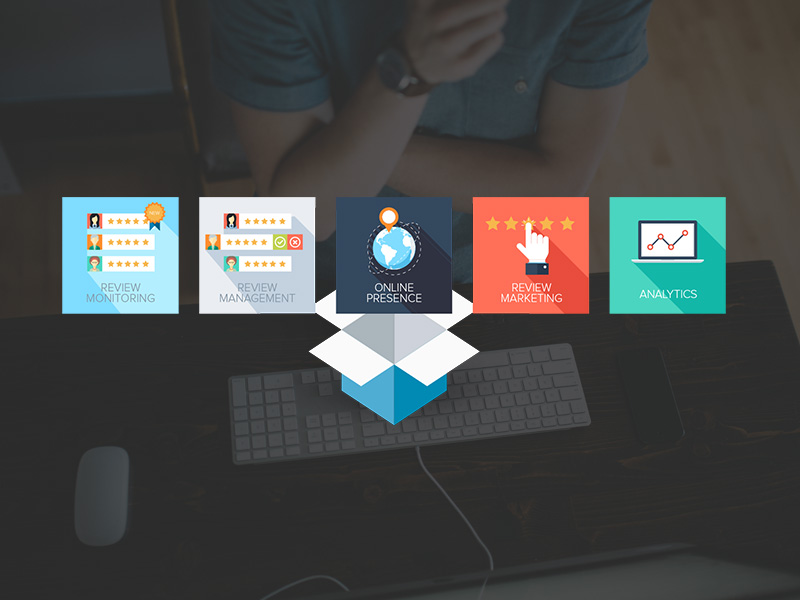

In response, services have emerged that help companies track and manage their online reviews. They offer tools to monitor reviews, multiple ways to attract positive feedback from customers and the ability to publish those positive reviews on several websites.

Birdeye is one such company offering these services. We interviewed co-founding CEO Naveen Gupta, a Silicon Valley veteran, on the state of the industry.

How many review sites now exist online? We track more than 100 review sites. I believe there are thousands, but only about 100 are influential. Of those, 50 or so are applicable to every type of business. The rest are in vertical markets — niche sites dedicated to specific industries like dentistry, law or finance.

Which do you consider the most important? Tier 1 directories like Yelp, Google, Yahoo, Facebook, Twitter and Yahoo have the most traffic. In Tier 2 are the verticals – sites devoted to specific industries. Avvo, a site that ranks and reviews attorneys, is in this tier. Tier III sites are general business listings such as Yellow Pages, Insider Pages and Super Pages.

What do you consider the most common misunderstanding of business owners about online reviews?

What we see across all verticals is that businesses small and large have been caught unaware of customer feedback because of the proliferation of review sites. As a result, they don’t know which sites to participate on. Depending on your type of market, the importance of the sites differ. Often, business owners don’t know where, and when, their reviews have appeared.

Authenticity of reviews is a concern. Many sites are not good at validating the identity of users. Or the customer’s review does not include the full issue – just their take on it.

Remediation is another big issue we see. Most review sites are not remediation vehicles. They are just one-way venting platforms. Studies show that happy customers generally don’t write reviews – only the unhappy ones do. Unless business owners actively encourage their feedback, satisfied customers don’t provide it. Proactive services enabling business owners to attract them have become necessary to succeed in this environment.

Review sites are often accused of manipulating results so that only negative reviews show up unless businesses pay a fee to the company. What advice do you give to business owners in such situations?

Not every business owner feels they have the time or resources to invest in managing their online reviews. Yet, your brand is your #1 asset. Don’t outsource it. Pay attention. Rather than focus on ratings, invite and focus on the feedback from your customers. Then address it. Use tools to automate the process. It’s about providing great service, correcting any problems and turning your customers into your advocates.

Larger enterprises and franchises are more concerned with monitoring reviews across the spectrum, comparing customer satisfaction across locations or regions, then feeding the data into their systems so they can make customer management adjustments.

There are new tools to help business owners manage all of this. It has become nearly impossible to handle manually. Fortunately, that is now unnecessary.

Naveen Gupta has had senior executive roles at RingCentral, Monster, Yahoo and UTStarcom. He studied in the Executive Education program at Harvard Business School; has an MBA, Finance from NYU Stern & London Business School; and a B.S.in Electrical Engineering from BITS Pilani.

This is the first in a series of interviews with experts whose work relates to online reputation management.